Several years ago, Interactual Limited designed and built a kinetic installation for a designer shoe brand as a feature in their flagship store in Covent Garden. We were invited late to the party – another sub-contractor had let the lead contractor down at the 12th hour.

The installation comprised 21 Perspex boxes on cables in a grid 3 x 7. Each box moved independently from near the floor to close to the ceiling and was internally lit with independent control of the lighting in each box. The intention then was that the boxes would be programmed to ‘dance’ with a number of different patterns of movement and light.

We had 3 weeks before the shop's opening party to design, build and install, into the ceiling void, 21 identical mechanisms. Somehow, we did it (I still don’t know how!)

A short time after the beautiful people, fashionistas and influencers had recovered from their launch party hangovers, the shop manager approached me directly to discuss the issue of post-installation support. As tail end Charlie in a very long chain of sub-contractors this approach was a bit of a shock to me, but it turned out that no one else further up the chain had even considered what happened after.

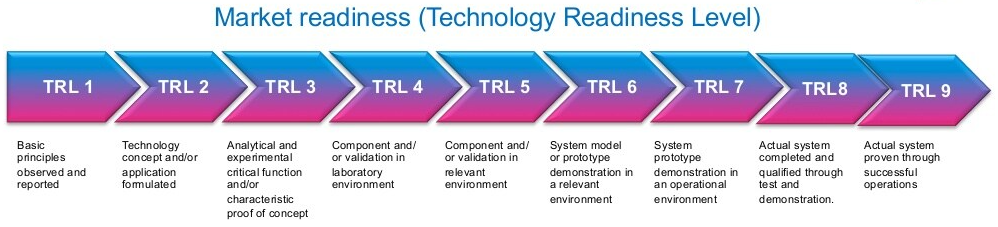

The Manager asked for a warranty. Seems reasonable enough. After all, pretty much everything else in the shop fit-out was warrantied. Even the humble light switches had factory warranties. The thing about those light switches is that, in order to offer a warranty, many pre-production and early production units would have been subjected to life-cycle testing to a number of on/off switching cycles way beyond the expected number of switches that one switch would be expected to endure in a typical lifespan. They would have been tested under extreme environmental conditions of temperature and humidity. Particles of abrasive material would have been introduced to accelerate wear.

The system we built was installed with minimal testing. All we had time to do was to check that everything worked at time of installation. But even if we had had the luxury of time, we couldn’t have done sufficient life cycle testing to be able to guarantee continuous function over the intended life of the installation. Why? Because the installation was running 7 days a week, 12 hours per day. If we consider again the light switches, these are maybe used once a day. So, over a period of 10 years, that would still only be 3,650 operations. The lifecycle testing would have the switch thrown off and on maybe once every 2 seconds. So, testing equivalent to 10 years of use could be carried out in just over 2 hours.

But when use is continuous, how can lifecycle testing be completed without taking 10 years to test for a 10-year life expectancy? There are some tricks for accelerating life-cycle testing using, for example, temperature or humidity but in the case of this installation all that was academic – we simply had no time to test at all before launch.

What to offer instead of a warranty? A fall back can be the manufacturers warranties for individual parts in a device. But frequently we’re using parts in applications for which they were never designed. The cable drums in this case were designed for electric garage doors and the shaft contacts were spare parts from Ford Mondeo alternators!

What we offered instead was a rapid response service whenever the system failed. Our only access was between 8pm and 8am as the shop was open 7 days a week. We maintained a stock of 3 complete spare mechanisms as this was the maximum number we could switch out in a single visit. Our approach was to switch units and not to attempt any repairs on-site and then to triage and repair faulty units back at our workshop. We charged time and materials at a fixed hourly rate.

This system worked well for the first 18 months. But then the units started failing almost faster than we could replace and repair. It was small comfort that the fault was not of our making – to reduce the risk of potential failure, we had specified the drive motors, the motor control units and the PSUs as a package recommended for use together by one supplier. It turns out that the PSU was the weak link with a shorter-than-stated life of only 18 months. It was no surprise that when we sought out replacements, the supplier had substituted these PSUs on their website.

Once the PSU’s had all been replaced, our visits dropped to a couple per year and the system functioned continuously for 7 years at which point the lease on the site expired and the shop closed. Not bad for a system built without any design development or iteration in just 3 weeks!

In more recent times, Interactual Limited has designed and built numerous lifecycle test rigs for use by customers at their own facilities. For us these present similar challenges. If a lifecycle rig is expected to operate continuously, how then to test the life expectancy of the rig itself or determine MTBF of the individual elements of the rig? How can we determine an appropriate frequency for preventative maintenance and what needs to be replaced as a preventative maintenance activity if we can’t run the rig ourselves for a duration greater that the expected lifespan of the primary components?

The challenge for us is that our clients want complete reliability from a custom built one-off. Very often, the rigs support long duration tests where the risk is a complete loss of useful data if the rig fails. The likelihood of failure is unknown, and the potential cost of failure is high.

So, when is a product not a product? When it’s lifespan and reliability cannot be guaranteed at delivery. Instead, delivery of a completed system, rig, demonstrator or device is just the start of a journey of collaborative engagement and support over the expected lifespan.

There is one area of risk in which a delivered prototype cannot be treated differently from a product and that is product safety. But that is a complex subject deserving of a separate follow-on article – watch this space!